Brian Friel's Compelling Faith Healer

“Faith healer–faith healing. A craft without an apprenticeship, a ministry without responsibility, a vocation without a ministry. . . occasionally it worked . . .”

Frank

“He was a convoluted man.”

Grace

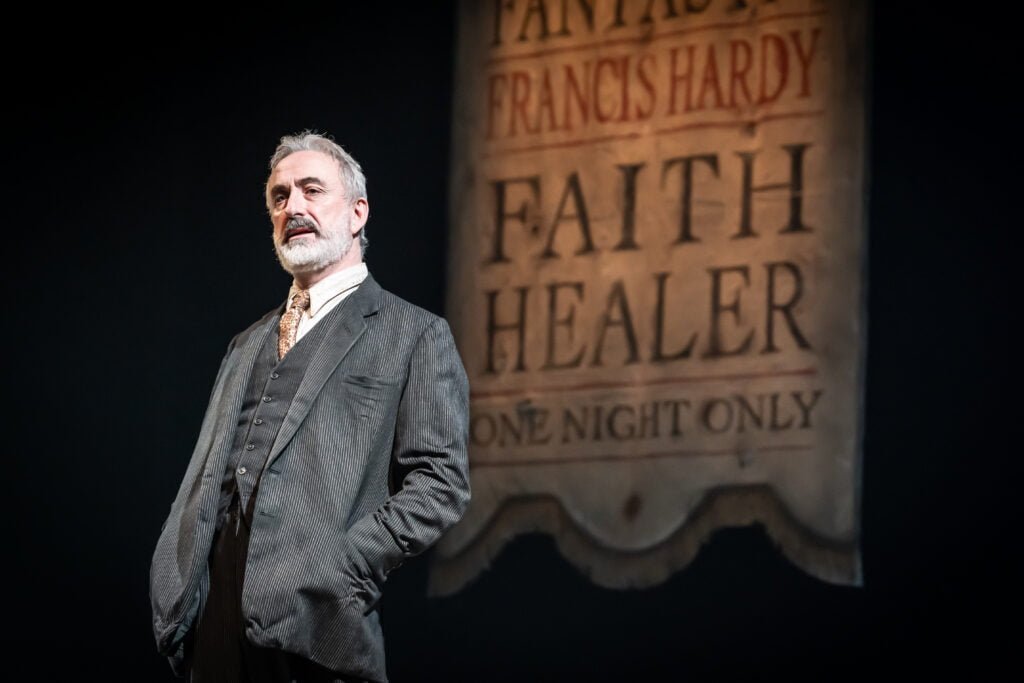

A man stands on a bare stage and talks to us as if we’re acquainted. Friends even. His talk is discursive, candid, serious, but also defensive. As if he is in a confessional. In fact the stage isn’t bare, but a long-deserted chapel.

A woman talks to us bravely, intimately, shamelessly, as if we are her therapist. And might forgive her. Might take away her pain.

A man talks to us as if we might buy him a pint. Or give him a job. Or at least listen to him…

What are we doing here? Who are these people?

We came to be entertained. These people are testing us.

One of Prince Hamlet’s many problems is should he trust the words of a Ghost? In Kurosawa’s Rashomon competing narratives of a violent crime are resolved when the murder Victim himself testifies from beyond the grave. But is even he telling the truth? Why should we expect the dead to be more honest than the living?

Faith Healer presents three accounts of the relationship between Frank (Declan Conlon), Grace (Justine Mitchell) and Teddy (Nick Holder), who travel through the British Isles offering healing services to the poor and needy.

Frank is the ‘talent’ – the Healer whose ministrations only ‘sometimes work’. Teddy organises their tours, drives their Van (‘untaxed and uninsured’), and confuses the punters by playing Fred Astaire singing ‘Just the Way You Look Tonight’. Grace is Frank’s partner – sometimes ‘wife’, sometimes ‘mistress’ when Frank wants to humiliate her – who takes the money at the door.

Like their not so distant kin, Hamlet’s Players, and the travelling entertainers in Bergman’s Seventh Seal, they live on their wits, and see the world differently from the locals they meet. But they are also emotionally dependent on each other and face different dangers. Tragedy awaits when the Van ventures back to Frank and Grace’s Ireland.

The three characters tell their story in four separate monologues. But… Why? How? From where? One of them is already dead, another soon will be, and the third isn’t looking too good. And they contradict each other in substance and detail. Who to believe? If anyone…

Does Frank really have the power to heal? Does that uncertainty torment him? Does Teddy believe Frank has the Power? “Honest, I have nothing to gain from this…” he says, before describing a highly improbable 10-punter healing session performed by Frank which will surely profit them both. If true…

Frank scrunches up the spurious news item which reports the event. And gets his name wrong.

Are Teddy’s dreams of wealth really scuppered by the sexual indifference of a bagpipe playing dog?

Is Grace ‘barren’ as Frank claims, when her horrific description of labour and stillbirth in the back of the Van is corroborated by Teddy? Is she truly appalled by their sadomasochistic relationship? Or does she accept that, “I’m one of his fictions. And I need him to sustain me in it?”

Perhaps the suggestion here is that Frank is a performer in a theatre of popular need. He can confirm to people that they have no hope. A performer with profound anxiety which only death can banish. The only kind of martyrdom left in a world where religion is absent.

“Bloody artistes!” is Teddy’s judgment on Frank, his breadwinner. Which reinforces his dictum that Managers should never be friends with Talent. But perhaps ‘the Teddy doth protest too much’.

Experiencing the play is like slipping into a fast-flowing river of words. It does not rest or stop but carries you along. (Except for a brief interval made all the briefer for the crush on the stairs.) You must attend to every word to keep afloat. It is an immersive, if sometimes bewildering experience. There’s no time to clutch at a speaker’s evidence, opinion, or emotion, and compare it with the next speaker’s, or the first’s when he reappears. It is hugely demanding work for the great trio of actors who run their verbal marathon alone on the stage in minimal sets which evoke an empty church, a paint-peeling metal wall, a tiny bedsit, a seedy hotel room. Or are they antechambers of a kind of purgatory?

The characters obsessively recite a litany of the villages through which they have travelled as if physical location offers some kind of stability. Embracing something like martyrdom, Frank is only aware of the reassuring shape and solidity of the building he sees. Not what waits inside for him.

The definite article is pointedly missing from the Play’s title. Is it Faith that needs healing, rather than the troubled story of a troubled man with that job title? Is Brian Friel making the point that, having abandoned a theological perspective on life, none of us can ever know the truth of what we too easily call reality? That we experience our lives as if assailed by the hints and whispers of an hinged broadcast media which can switch channel at will and cannot be turned off? Or is that too pessimistic?

Agree or not, this is certainly a demanding piece of work. And asserts the importance of living theatre.

Production Notes

Faith Healer

Written by Brian Friel

Directed by Rachel O’Riordan

Cast

Starring:

Declan Conlon

Justine Mitchell

Nick Holder

Creatives

Director: Rachel O’Riordan

Designer: Colin Richmond

Composer: Anna Clock

Lighting Designer: Paul Keoghan

Sound Designer: Anna Clock

Information

Running Time: Two hours 40 minutes with an interval

Booking to 13th April 2024

Theatre:

Lyric Theatre

King Street

Hammersmith

London W6 0QL

Box Office: 020 8741 6850

Website: lyric.co.uk

Tube: Hammersmith

Reviewed by Brian Clover at the Lyric Hammersmith

on 20th March 2024